September is Sickle Cell Awareness Month, and it’s also the month 8 years ago when I was given the privilege of starting to care for a group of people who will always be very close to my heart; that group is composed of people living with sickle cell disease. Given the significance of the month, I’m reflecting a bit on my experience as a sickle cell doctor at the Forefront, University of Chicago Medicine.

Me: “GET OUT! I have like 37% Hemoglobin S blood in my body right now? I’ve just been walking around with that all this time and didn’t know? WOW!”

My physician: “Yes. You seem particularly excited about this.”

Me: “Well, yes. You know I’m a Sickle Cell doctor. This is what I do all day, talk about sickle cell. For me to just randomly find out that I have sickle cell trait is kind of a big deal.”

And so it goes that I learned that I had sickle cell trait, joining the 1 in 12 Americans and 8% of Black Americans with this finding, as well. I then proceeded to proclaim that I would now have a perfectly reasonable excuse for avoiding skiing and scuba-diving, and said in jest that I would have to think long and hard before I would consider completing another half-marathon.

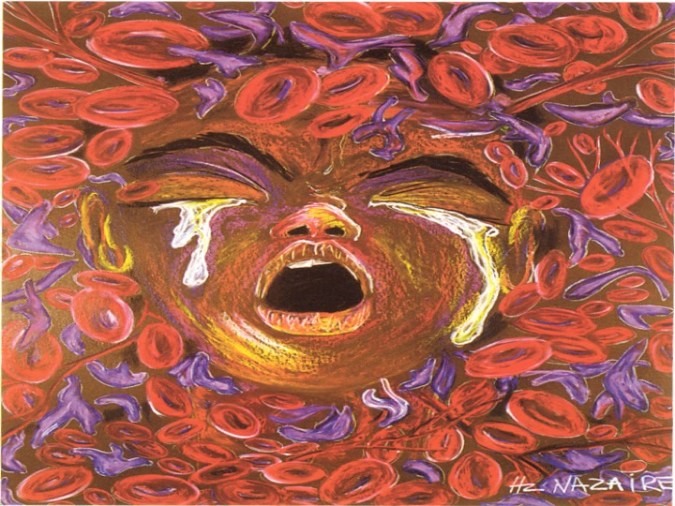

The difference for me from my patients, however, was that I had the luxury of talking about simply possessing the trait that would not have major implications for my life; at no point was I ever going to know the devastating pain, the life-altering complications, or the psychosocial anguish of the stigma associated with sickle cell disease. That pain is severe and comparable to cancer pain, and is recurrent, chronic, and disabling for most people living with sickle cell disease. The picture at the top of this post is called ‘Ten Redefined’ and is a graphic representation of what a 10 out of 10 on the pain scale feels like for a patient with sickle cell disease. This painting was done by an artist with sickle cell disease, Hertz Nazaire.

Though there were some aspects of my role as a director of a sickle cell program that I fully anticipated learning, I had no idea how much the experience would not only change my interactions with patients, but also provide perspective about health disparities, healthcare, and my general career path as a whole. In medical training, we are forced to contend with learning everything there is to know about the human body and physiologic processes and then, what happens in the seemingly endless various pathological states; so it is easy to get caught up in the science of medical care during rigorous learning. What most of us hopefully strive to do by the end of residency training is to start to incorporate the art of medical care and humanism into what we provide at the bedside. However, there are some patients who have multiple chronic or complex conditions that are so complicated that even ongoing research and established standards of care have precluded finding options for treatment that are particularly satisfactory for patients or providers alike, and this sometimes creates tension between the art and science of medical care and with the humanism for which we strive. And, in this area of tension, is exactly where sickle cell disease and those living with it exist. And that aforementioned explanation is what I needed to create for why there is bias against people living with sickle cell disease from the medical community.

When I started my journey into the world of dedicated sickle cell care, I felt I had gained pretty significant experiences from my background. I had grown up on a farm and attended a historically black undergrad (#FiskForever) and med school (#MeharryMade), and was most certainly aware of the plight of the underserved from a variety of experiences. I had taken care of patients who had little access to healthcare or resources to address medical concerns until they were uncontrolled or had proven nearly fatal. Anyone needing a crash course on the impact of the social determinants of health can access one any day by taking a walk down Jefferson Street between Tennessee State University, Meharry, and Fisk in North Nashville and observing the environment; however, given the economic boom Nashville is undergoing, gentrification may soon extinguish this said crash course, but I digress. I had then trained in Cincinnati in both Internal Medicine and Pediatrics and spent 2 years in inner city DC as well as 3 more years back home in Memphis in Orange Mound, leading a clinic in one of the most impoverished and under-resourced areas in the city. What I had learned in those practice experiences, though, was that people will invest in themselves, their communities, and in the doctor-patient relationship if you are willing to do the same. I had also learned that people are so much more than their past medical histories, their med lists, and even their social and family histories. Every person has a story, and in that story is woven these social determinants. What is now very plausible to me is this scenario for a patient: a lack of education because they lived in a dangerous neighborhood and couldn’t get to school without being accosted by gang members to join them; all of these issues feed into poor employment, lack of financial resources, and these issues marry living in food deserts and lead to having people with poor options buying salty chips as meal options when they already can’t afford to pay for meds for hypertension and they are dealing with PTSD from adverse childhood experiences, so they are self-medicating with nicotine and alcohol. I thought I had it all figured out when I wandered into Sickle Cell World, but I only knew the tip of the iceberg…

What I would learn from my sickle cell patients is that, once they were no longer children and could advocate for themselves as adults by requesting pain medications based on 18, 20, 30, 40 years of living with a chronic, painful, debilitating disease and knowing what works to help to reduce (most often not alleviate) that pain, they would be labeled as a “drug seeker.” Imagine if you expressed that you had trouble walking and were in excruciating pain, and people dressed in scrubs and white coats who are supposed to care about people crying out in agony said you were “faking it” because you would intermittently fall asleep amid requests for pain medications; what isn’t taken into account is, having been up all night in pain and missing sleep during pain crises, meds used for treatment cause severe drowsiness and somnolence. And what was most hurtful to hear from my sickle cell patients was that nobody was ever going to care about them because their skin was black. It’s hard to argue with people who are telling the truth. This is not the place to delve into the disproportionate and historical lack of federal funding for sickle cell disease as a more prevalent genetic disease affecting blacks than that provided to less prevalent genetic diseases affecting non-blacks, but one cannot possibly talk about sickle cell disease without addressing the inherent bias against its sufferers due to race, when racism is a foundational issue in this country. I recently attended a health equity conference in which someone said that sickle cell disease is really the prototypical health disparity. This perfectly summarizes my thoughts about being a sickle cell doc, and what this disease means in terms of race and health disparities in America.

On the flip side, however, I would learn that you don’t have to be black to care about people living with a “black person’s disease.” I was very fortunate to have walked into a program that had been started by a former hospitalist at University of Chicago who saw a role for a care model that could address some of the needs for the sickle cell population on an outpatient basis and therefore, get to the “triple aim” and address not only the experience and quality of care for the patient, but also the cost of that care to the system as a whole. What was that physician’s race? White. In fact, what was the race of the nurse practitioner I joined to take over for that physician, as well as the social worker who worked with them? Also white. And the same goes for the nurse practitioner I eventually hired when our original NP left, as well as the amazing Department Chair who both championed the program and hired me for the job. And I could not have asked for a more fierce team of advocates for our sickle cell patients or a more supportive, brilliant, and collegial group of fellow academic internists, proving that compassion can most certainly transcend race.

Being a sickle cell doc taught me about the business of medicine. I suddenly became very popular among hospital committee members when I started taking care of patients with sickle cell disease. It turns out that sickle cell care is, indeed, expensive. This is when I would earn a personal quick degree in utilization management, and I would begin to understand how it plays a role in managed care, which has now become a career focus. My foundation for my current work was built upon meetings with transfusion, high utilization, diversity, and medication safety committees. The fortunate part of this experience was that the institution, the University of Chicago, situated on the South Side, also promotes and supports the importance of being connected with the community. Therefore, there exists a good balance of addressing the business of the hospital with that of the community, by participating in community health events while making presentations, providing education, or assisting with donation events.

Being a sickle cell doc’s most important lesson was how to be a passionate patient advocate. This would prove to be important not only for my patients, but personally, when I made the decision to leave after 3.5 years, so that I could move home to Tennessee to be a patient advocate and “Dr Daughter” (my father’s term) for my dad when he was diagnosed with a terminal illness. When taking care of people who spend countless days, weeks, sometimes months of their lives in the hospital with a disease like sickle cell, you cannot help but get attached. It would be nearly impossible not to imagine what it must be like to be given a diagnosis like sickle cell; it means facing a high risk of stroke during childhood, recurrent painful episodes throughout a lifetime that typically lasts only until the mid 40s, and potential complications of every possible organ system from head to toe. On top of all of the physical medical problems associated with the disease, the psychosocial hardships accompanying this diagnosis seem almost insurmountable. And yes, people with sickle cell disease can be a challenging group of people to care for – it is not a world full of unicorns and rainbows when taking care of people whose hallmark disease process is characterized by pain. I have had some of my worst days in clinic or in hospital suites with patients and family members explaining that everything that could be done is being done, but that “if you would just take this medicine every day, you might not have as many hospital stays.” But everything is about perspective. I don’t know what I would do if I had missed most of my years of school or work because I was confined to a bed with a pain crisis. I do know that we did have patients who did everything the way they were supposed to do them – they took their meds religiously, did not get overexerted, stayed hydrated, and they still succumbed to the cruelty of this disease anyway. I have taken care of a great deal of patients over the years and I have seen babies, elderly, and people of all ages pass away from horrible medical circumstances. However, my most challenging experiences with death in my medical career have been during my time with our sickle cell team; developing a heart for sickle cell patients means also being vulnerable to having that heart-broken when a patient with whom you bonded so closely transitions. What I learned from my sickle cell doc years was that sickle cell patients are like everyone else; they just want to be heard and they want to be validated. They want to know that you understand that they are doing the best they can, knowing that their time here on earth is significantly limited compared to their peers. They also want people who know better, like people who understand more by knowing them and their lived experiences, to do better. So they taught me that it is not good enough to simply teach my colleagues and medical trainees about the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. I have to do better by calling out the fact that there is racial bias that precludes sickle cell patients from getting the pain relief and appropriate care they need when they seek emergency and inpatient treatment. They taught me to speak out for them and to be a bullhorn for people who may not always have the opportunity to spread awareness about this terrible disease and the possibility of a cure.

THERE IS A CURE FOR SICKLE CELL DISEASE.

What is that cure? A bone marrow transplant. It is especially difficult for people living with sickle cell disease to find donors for a multitude of reasons, but particularly because more minorities are always needed to sign up to provide the possibility of finding a match. Signing up is easy and takes just a few minutes at: http://www.bethematch.org.

If you take nothing else from this lengthy post about my time as a sickle cell doc, please consider signing up to be a bone marrow donor. That one act could not only help cure someone living with sickle cell disease, but it might also be the answer for a child fighting cancer, and September is also Childhood Cancer Awareness Month. More to come on this subject at a later date. In the meantime, please checkout the Be the Match website today!